Computational Textiles

This is super cool-if I could afford the hardware, I would certainly be buying this to tinker around with:

http://www.knitty.com/ISSUEss10/PATTknowitall.php

If you’re not a knitter the point may be a little obscure, but just trust me, it’s cool. And be sure to watch the youtube video of how it works:

http://www.youtube.com/watch#!v=iFOvtzAwGrw

This is the awesome blog of this project’s extremely smart creator:

Go and be awed!

Stephanie Strickland

This reading struck a chord with me this week, because I’ve been doing a lot of thinking about what it means for a digital poem to be present somewhere other than the screen. This is important for my final project, and Strickland’s poems confirmed for me that these digital poems can exist outside the cocoon of the electronic. I looked at the online portions of Strickland’s poems first, and for reasons I can’t explain, I was much more interested in the physical text versions that appears in the book. If I was asked to explain it, I would have to say the blame lies partially with me. I’ve had a frusterating week with technology, so I’m not feeling particularly charitable towards computers right at this moment. Also, I just love books. I don’t mind reading on line, and I often do so for convience’s sake, but as a visual artist I love the weight, the feel and the smell of a book in my hand. I also think that the outdatedness of the interface may have had something to do with my reaction to Strickland’s work online. As we discussed last week in class, the interface is of the “uncool 90s.” Also, if you are trying to do certain kinds of random reading, they are actually easier, or at least somewhat more impactful in the book. For instance, in the Losing L’una set of poems, one of the things that kept me interested and reading was the interplay between the text and the numbers. I read the poems once straight through, and then I tried to go back and read them in numerical order. It isn’t possible, and there are a certain numbers that repeat several times, but in the process of flipping through the text, trying to line up and keep track of the numbers, I felt the forbidden thrill of breaking the rules, of reading out of order in a way that is simply not possible for me in clicking on a series of computer links in a non-linear way. The computer is set up in such a way we are trained to use it in a non-linear fashion. I expect to be able to take a experience the content in any way and any order I chose, to the extent that I feel restricted if I can’t. I have been trained to read books in a certain way since childhood, and that illicit thrill of skipping pages and reading out of order enhances the experience of reading Strickland’s poems on the page, rather than on the screen.

You are…conceptual poetry

In reading the introduction to Charles Hartman’s “Virtual Muse” one of the things that caught my eye was this: “Poetry is something we do with language. Or rather its a lot of different kinds of things we do with language. It’s a place where we can attend to language.” This very vague statement was somehow mysteriously appealing to me, and it very much seems to describe what is happening in both conceptual and computer generated poetry. We’re “doing something” whether we know what that something is or what it will accomplish, we’re keeping poetry alive and moving it forward, refusing to let it be Marinetti’s dead, decaying museum of culture. One example of poetry doing something is Kennedy and Wershler’s “Apostrophe (ninety-four).” Although on the surface it is simply a series of “you are” statements, I found it captivating and engaging my mind, and in the way that the best poems do, inspiring original and creative ideas in my mind. Some of these statements are legitimately funny, “you are having a paranoid delusion that a figure much like Henri Matisse’s Blue Nude is following you around trying to get you to join the Jehovah’s Witnesses,” in particular, made me laugh out loud, but when one stops and starts to deconstruct the web of references that are necessary for this joke, one starts to realize how complicated this poem really is. One must be aware of popular or at least pop culture representations of schizophrenia, know who Matisse is and what his Blue Nude looks like, and who the Jehovah’s Witnesses are, and that they typically try to recruit door to door. One definition of art that I was taught as an undergrad studio arts major is that “art is making connections that other people don’t make.” This one example from Kennedy and Werschler’s work makes all sorts of connections that other people don’t make, and it does something with language to make me think about the juxtaposition of those things, and the large amount of referential material that I’m familiar with that I find this example really funny. And then there are all of the other examples in this poem. Some of them are beyond me, they involve mathematical or scientific language and examples that I haven’t thought about in years, if ever. Still this poem, as simple as the form and concept are caught and held my attention through pages and pages of “you are” statements, and it made me think and make connections. It made me do something with language, and even as simple as it seems, this makes this poem succeed for me.

Conceptual Poetry

“On the conceptual side, it’s the machine that drives the poem’s construction that matters. The conceptual writer assumes that the mere trace of any language in a work—be it morphemes, words, or sentences—will carry enough semantic and emotional weight on its own without any further subjective meddling from the poet, known as

non-interventionalist tactic.” -Kenneth Goldsmith

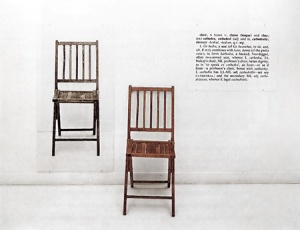

I love the idea that any mere trace of language in a work will carry a semantic and emotional weight. Maybe because I’m not a poet or a fiction writer, so I don’t feel the drive for my writing to be creative or necessarily break new ground. However, this idea that any trace of language will carry through and somehow draw attention and weight to itself has a lot to do with points that I have made earlier about the inevitability of the human drive to search for patterns. I’m a strong believer that humans will always try to create patterns, even when none exist, and that there can be beauty and interest, even in the patterns of coincidence. For this reason, one of my favority pieces of conceptual art, and perhaps conceptual poetry, is Joseph Kosuth’s “One and Three Chairs.”

As charming as I find the actual piece, it is the title which has caused me to smile. The piece itself operates as a demonstration of Saussurian semiotics, but the title to me is poetry, and it lets me see the weight, and think about the objects and the text here.

One of my favorite things about this piece is that its appeal is not universal. I have taught this several times in intro art history classes, usually to students that despise it. Like a lot of digital poetry, this piece takes time and thought and effort to appreciate, it is something that grows on you. I’m not sure how this relates to digital poetry, or to anything we read this week, but I think its interesting and connected even if I don’t quite know how.

Suzan-Lori Park’s “Venus”

This play was very contemporary, and took full advantage of the ability of modern playwrights to experiment with staging, pace and tempo in drama. Its subject matter also necessarily deals with issues of race, gender, and sexuality. The issue of race follows many of the expected tracks when the subject under discussion is a black woman who is exhibited for a white audience. The issue of slavery is certainly present in the background, as is the issue of sexual relations and sexual attraction between the black and white characters. However, one of the aspects of the race issue that was most interesting to me was the extensive use of chocolate throughout. The Venus character is motivated to perform certain actions throughout the play by being given chocolate, and at several points chocolate is associated strongly with love. However, the associations between chocolate and love and chocolate and Venus must point the reader in the direction of interracial sexual relations, a problematic subject in this text, as the interracial sex taking place has definite overtones of coercion and slavery. The use of chocolate in this play is further complicated by scene 3 “A Brief History of Chocolate.” This scene reminds/informs the reader as a substance originating in the Americas, and one that was associated with religious ritual. This scene seems to me to complicate the way that chcolate is used in the play even further. On a very simplistic level I suppose that one could equate the “primitive” tribes of Africa with the “primitive” tribes of the Americas, but that feels reductionist and overly simple for a playwright who succeeds in bringing up a whole host of other issues in a much more subtle way.

Concrete Poetry and Gibberish

The premise of this video is that it sounds like spoken English to Italians (In the same way that the noises that Mario makes sound like Italian to English speakers). While this isn’t necessarily a form of concrete poetry, this use and exploitation of language seems to be somewhat related to Futurist and Dada sound poetry.

http://www.youtube.com/v/Ov_UksYViOc&hl=en_US&fs=1&”></param><param

This video plays with gibberish and nonsense in the same way that some of the other examples that we’ve looked at so far. It also seems to be somewhat related to concrete poetry as well. This is an English translation of the video:

value=”http://www.youtube.com/v/Wz04IBZqfFE&hl=en_US&fs=1&”></param><param

Although the subtitles are sometimes a little off for what I hear in the video, the way we go about creating meaning from this nonesense seems to resemble, for me the way that we create meaning from concrete and nonsense poems. Even when there is no meaning, or the meaning is perhaps not clear to us (concrete poems which use languages we don’t speak, for instance), human beings are programmed to try to create pattern and create meaning. In the same way that we create meaning out of this video, we see and recognize patterns in concrete poetry. An example of this is Haroldo de Campos’ untitled poem from 1958: http://www.ubu.com/historical/decampos_h/decampos_h1.html. I’m not sure of the meanings of the Portugese words here, but I cannot help but equating them with their English cognates, whether those cognates are true or false. Thus, in looking at the particular example of concrete poetry I have constructed in my head a reading that is about the transparency of form and the transparency of meaning on concrete poetry, without knowing if this meaning has any relationship to the actually meaning of the poem, the actual words on the page, and the actual intent of the author. Although as a historian, this posistion is frusterating to mean, because I want to know what it means and have it be historically situated and backed up with evidence, as a literary critic whose views have been shaped by modernism and postmodernism, this reading seems as valid to me as any other. So I’m left in limbo.

Frank Portman’s King Dork

While I thought moments of this book were very funny, I was mostly annoyed by the book. I don’t know if its because I haven’t read “Catcher in the Rye” in years, and am not part of what Portman calls the “Catcher Cult.” I can see that many of the things in this book are meant to be references to “Catcher,” but I’m not close enough to both books to make the connections, which mainly makes those connections have the irritating feeling of a reference that is slightly out of reach. I also felt with this book, like with “Feed” by M. T. Anderson, that this is a book written by an adult for other adults dressed up as a YA novel. The constant references to 70s music, as well as the curious absence of appropriate technology, make this seem like the author is imagining his 70s adolescence as it would have happened in the 90s. This also something that feels true about the central premise, the retelling of “Catcher in the Rye” for a new generation. I don’t think “Catcher” is as important a book about teen alienation, or at as singular of an example in the 90s as it was in the 60s or 70s. I didn’t identify with the protagonist, and I don’t think his situation is one that would be widely identified with by contemporary teenagers. In the age of the internet everyone can find people with similar interests. Also, by the end of the novel, the character has swung too far to the opposite extreme. He’s not popular, but he has a place in the social structure of his school, and he’s getting three blow jobs a week from “semi-hot girls,” in what seems to be an unnecessary touch of misogyny.

Teshome Gabriel, Nomadic Aesthetics and Black Independent Cinema

I found many of Gabriel’s arguments about Nomadic culture and black cinema fairly problematic. First, he starts off by conflating all nomadic cultures, and categorizing the contributions of all nomadic cultures in two sentences. While I find his assertion that an aesthetic “without frontiers or boundaries” reductive and problematic, I also like it (396). However, I’m not sure that I actually like the idea that Gabriel is trying to express, and instead I have a sneaking suspicion that what I like may be instead a romanticized idea of the nomad, created by the power that Gabriel is writing against, the power of Hollywood. Another idea of Gabriel’s that I find simultaneously alluring and problematic is his statement, “In black films there is often the depiction of journeys across space or landscape” (403). Claiming the idea of a “journey” as a space that is occupied by black cinema seems to at least imply the exclusion of other cultures. However, the story of a journey is one that transcends cultures, and is as old as literature itself, with some of our most famous examples of early literature being journey literature (thinking of the Odyssey, or the Anglo-Saxon poem “The Wanderer”). I think there is certainly a space within this tradition for black literature and black cinema, and the African-American community might have a unique space within the journey narrative, telling the story of the Middle Passage, but as always, the trick of multiculturalism is inclusion without conflation or degradation.

Concrete poetry and definitions

Since one of the on-going issues in this class has been struggling with definitions, I was really struck when I came across Solt’s definition of non-linguistic concrete poetry: “the non-linguistic objects presented function in a manner related to the semantic character of words.” Because one of the questions I have consistently struggled with is the relationship between the visual arts and digital poetry, I find this definition very useful. This definition lets me draw a line in the sand, and say that if a piece of digital poetry relates to the “semantic character of words” than I can consider it poetry, even if it doesn’t provide me with a recognizable text to draw from. Of course, this definition is problematic. How do we determine if a work is relates to the “sematic character of words” if there are no words for us to draw on? Concrete poetry, as well as the poetry of the avante-gard seems to rely on the presence of letter forms to indicate both phonetic sounds and that the resulting poem, even if it is not readable, is related to language. Digital poetry comes at a moment where this method has been so far undermined by the forms that I mentioned previously that it doesn’t necessarily need to use language at all. Some of it obviously does, for instance, “Birds Singing Other Birds’ Songs” is as much about how one hears and interprets the world through alaphabetic language as it is about birdsong. However, other examples simply present images or playable programs. These have been more challenging for me to classify as poetry, possibly because I do have a stronger background with video games than poetry in some ways, but I feel like this definition gives me a place to start looking for meaning and looking for connections between some of these more abstract digital poems and what I include in my definition of poetry.

David Henry Hwang, M. Butterfly

I have to start off by saying I loved this play. One of the things that I was very interested in is how relevant the issues and critiques raised by the play still felt, twenty years after its first performance. I think some of Hwang’s critiques, particularly those involving orientalism seem like old hat, particularly to an academic audience, there are other critiques that are much more subtle that make this play age well, where other plays, particularly issues plays (I’m particularly thinking Angel in America here) show their age at every turn. One of the things that I think make Hwang’s play so ageless is that it doesn’t do a straight reading of anything. Any time you think you might be on solid footing with a topic, there’s a twist and your perspective changes. I think possibly the most interesting thing that Hwang does for me is his critique of what we might call Western denialism. I think even in the late 80’s and the early 90’s Hwang’s use of Said and critique of the orientalist tendancies of western culture would be familiar to a western audience, but no one in the audience wants to admit that they have these feelings. However, I would be willing to bet that same educated, western audience is at least familiar enough with the music of Madame Butterfly that they recognize the famous songs, otherwise the use of the music would lose the majority of the effect. At the point where the music is working in its role in the play, one is forced to admit to an enjoyment of this opera, which on reflection is incredibly Orientalizing and racist.

There is a similar type of critique going on here with gender and sexuality I think. We all like to say that we are open-minded, at least typically in a liberal, academic setting, but we’re all also sucked into our curiousity about the sex lives of these two men. If Song Liling had truely been a women, this story wouldn’t have been half as interesting and sensational, and the focus of the newspaper story that inspired the play would have probably been directed exclusively at the act of espionage, rather than including the details of the sexual affair. This kind of curiosity provides the same kind of realization as the question of race does in the example above. When the reader or viewer realizes that they too are waiting for the details of how a man could have been sleeping with another man for twenty years and never realizing it, we are drawn into an examination of our own feelings about gender and sexuality.